By Manny Crisostomo

Peter “Pete” Gumataotao got his moral compass from his parents growing up on the border street of Tutujan Drive between the villages of Sinajana and Agana Heights and held fast to it as he navigated an illustrious military career in U.S. Navy, culminating in being the first CHamoru to achieve the rank of two-star admiral.

During a recent trip to Honolulu, I got a formal escort to the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies director’s office where I was greeted with a big smile and a che’lu hug from the 63-year-old retired rear admiral and now the institution’s director.

We sat down to reconnect and reminisce about our Guam school days that spanned from rambunctious first graders in elementary school to studious but equally prankish Father Duenas Memorial School brothers.

We also “talk story” about our similar upbringing, about our parents, the familia, the church, life lessons and the culture. And how growing up CHamoru and our roots manifest themselves in our life’s journey. “The fact you and I have this ability to reflect back on that in life just tells you how blessed we are,” he said.

In sharing stories that have a profound impact on him, Gumataotao refers to them as “oh wow” moments. He explains it as “something that’s not necessarily in your bio, it is something that you share something with somebody and they go, ‘Oh wow, I didn’t know that.’”

Augustin and Rosa Gumataotao gave him his more powerful and enduring “oh wow” moments. He calls his mother “Na” and his father “Ta.”

“When the Japanese came to Guam, she was in the concentration camp and si Na never talked ill about the Japanese people, not one ounce of that,” Pete Gumataotao said. “And the ‘oh wow’ of it is that I read this book long after Na died. It was called “Unbroken” and it talked about some of the not so good things about being in a concentration camp in war, specifically with the Japanese concentration camp.

“I put the book down after I read it and just looked up and said si Yu’os ma’ase Na. Because Na could have easily taught me the H word, the hate word and she never did. In fact, if I think about any of the stories that she shared about that time, it was pretty endearing and found some goodness in people.”

As an altar boy at St. Jude Church in Sinajana, Pete Gumataotao remembered funeral services for soldiers from the village who died during the Vietnam War. One afternoon he recalled watching a Walter Cronkite news report on anti-war protesters.

“They were doing something to the flag that confused me. The same flag that we folded over the coffin of somebody we knew who gave up their lives for this freedom. They were burning it and they were stepping on it,” Pete Gumataotao said as he turned to his usually quiet father and remembered asking why.

“He didn’t even hesitate, he said ‘Boy don’t worry what those people are doing to the flag, just remember what our flag means to us,’ And at that moment he taught me the value of not to judge, not to judge others, just be true to your own values and live it,” he said.

“Now that I look back in retrospect, it’s wow, that was big, not to judge others and not to hate my gosh that has served me well in my journey in life.”

His journey began when he took a PanAm flight from Guam to the East Coast. He graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1981 and earned his Master of Arts in Strategic Studies from the U.S. Naval War College in 1994.

He has been deployed as a surface warfare officer and to command-at-sea tours to the Western Pacific, Indian Ocean and Arabian Gulf.

There is much more to his resume of nearly four decades of distinguished military service but one of his highlights was in May of 2000 when he sailed into Guam with his crew of 332 as the commanding officer of the USS Decatur, one of the most advanced destroyers in the Navy’s fleet.

The Navy flew his wife, AnneMarie, and then Lt. Gov. Madeleine Bordallo on a helicopter to join him in the bridge when he pulled into Apra Harbor. Once moored, he entertained his four brothers, Joe, Pale Gus, Tony and John, and their immediate family in his cabin. More family, friends and his FD class of 1976 classmates came, as well as a group of wide-eyed high school JROTC students.

“Na was not physically strong enough to climb up the brow of the ship. She quietly sat in her car and watched as I pulled up to the pier,” Pete Gumataotao said. But they had their moment together at Guam Veterans Cemetery visiting the gravesite of his father, who passed away in 1975, the year before he joined the Naval Academy.

He said his father never pushed him or his brothers to follow in his military footsteps.

So he was shocked when his mother shared that when they were all kids, his dad said wouldn’t it be something if one of his boys not just joined the Navy, but joined the Naval Academy and became an officer.

Pete Gumataotao was at a loss for words looking over his father’s gravesite. Fighting back the tears he turned to his mother and asked “would Ta have been proud of what I had accomplished." Without hesitation she looked at me and said, “Son, he has been with you every step of the way.’”

Pete Gumataotao also speaks of his wife, AnneMarie, daughter Kailani and son Peter, who have been his support system but acknowledges the sacrifices they made. “There was a lot of hard work, and oftentimes a lot of sacrifice where you miss birthdays, miss anniversaries, just miss a lot of things you do as a family.”

He says his wife grew up in Saipan and they have the same values. They speak CHamoru to each other and teach their children the culture and the importance of respect, family and faith.

“I have been away from home so much and for so long, but I have this bond and this tie, as well as my family does, every time we go back to visit the family that tie is still there, it’s always there, it will never go away,” he said.

His kids love going back to Guam, and he says it’s magical for them to be with the aunts, uncles, cousins and even the “extended familia.”

“When they go back and they see that and then they see beyond the familia the culture of things and then they connect with how they were raised over here. They see it, they see the connection, they go ‘Wow, I am home even though I’m not home.’”

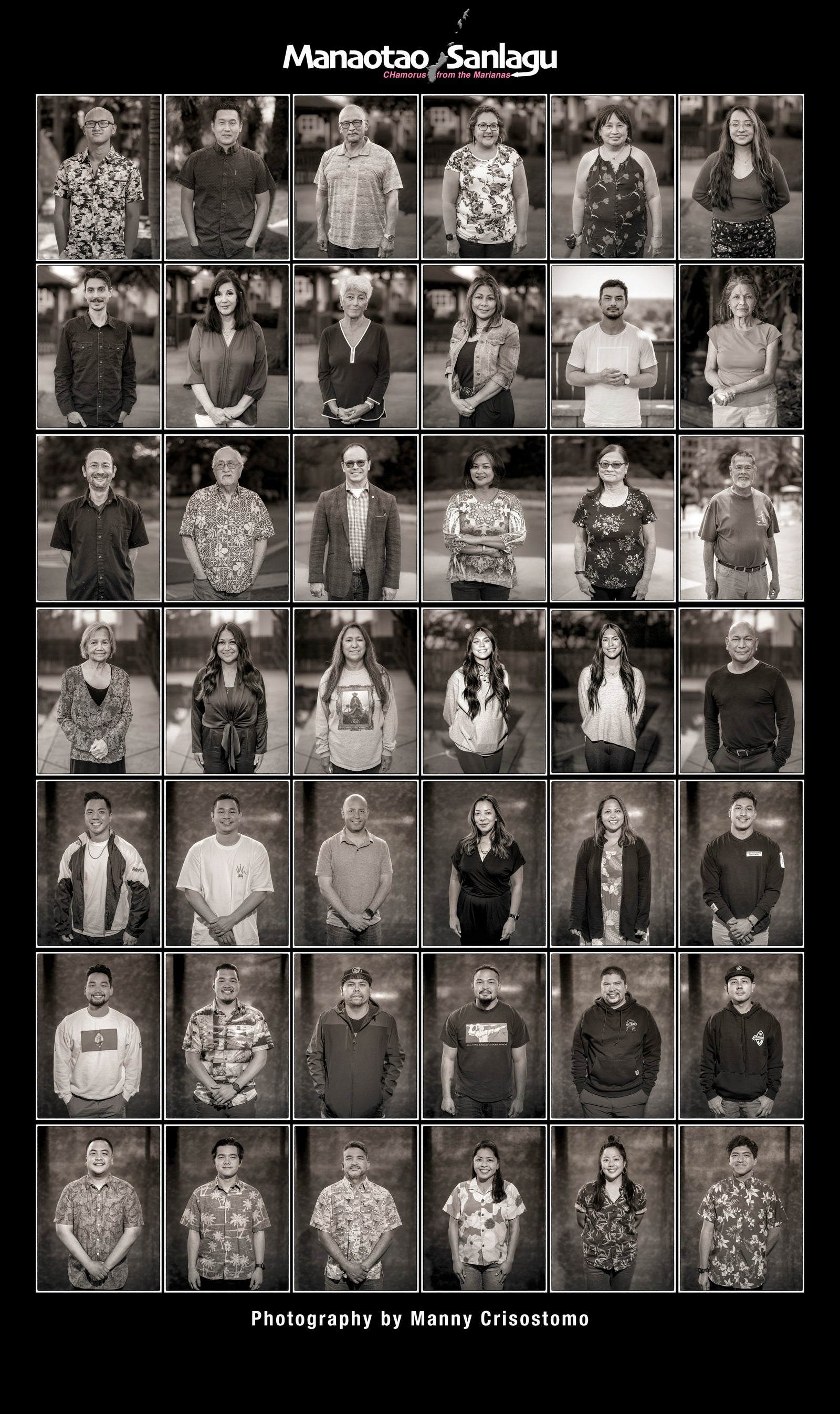

Manaota Sanlagu is Manny Crisostomo’s ongoing visual documentary of CHamorus from the Marianas living overseas that is featured weekly in the PDN. If you or someone you know would like to be part of this documentary or wish to support this project, contact Crisostomo at sanlagu.com. The project is sponsored in part by Brand Marinade, a CHamoru-owned creative agency in the San Francisco Bay Area.