By Manny Crisostomo

Lyn Aflague Arroyo grew up in an intergenerational CHamoru household eating grandma’s cooking and listening to grandpa’s stories while her parents were off at work. Her aunts and uncles lived nearby for additional familial support, and of course she had all those cousins to play with. On weekends there seem to be endless rounds of funerals, rosaries, weddings, baptisms or birthdays.

“My grandparents being with us, being around the aunts and uncles all the time, my sister and I were very much immersed in CHamoru culture. It just seems like every weekend we’re always with family somewhere here in the Bay Area.., it helped me as someone who (was) born stateside stay connected to the Chamoru culture, ” said Arroyo, who lives in San Ramon and works in outreach and recruitment at the University of San Francisco.

Arroyo’s upbringing is not unique among the 180,000 plus stateside CHamorus, many of whom have created enclaves in towns and cities across the country.

In many of the tight knit communities the CHamoru sainas, the elders, propagate kustumbren CHamoru. “Family and respect is the root of what I feel CHamoru culture to be, everything is about being respectful, respecting your elders,” said Arroyo, whose Bay Area extended clan of Aflagues, Duenases and San Nicolases carry on their elders’ teachings.

CHamoru identity

Arroyo fiercely defends her identity. “I consider myself CHamoru, I don’t consider myself a diasporic CHamoru, I consider myself a CHamoru that was born and raised not on her island. I have influences from here and I miss home, but at the same time I have been able to find ways to keep that connection,” said Arroyo, who was born at the Oak Knoll Naval Station Hospital in Oakland.

Her inner struggle seems amplified by her research and curiosity as a grad student working on her master’s degree in migration studies at University of San Francisco and her over 20 years working in education, community outreach and advocacy in the Bay Area, which gave her the opportunity to hear and learn from hundreds of migration stories.

Arroyo suggested we meet at the Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Hayward. “There’s something about talking story next to where my grandparents are laid to rest,” she said. “It was a place I often went to as a little girl with my grandma, my brother died as an infant and is buried there.”

Migration

In her thesis work, she said, “my focus is on CHamoru migration, focusing on my grandmother’s migration story and looking at that through a CHamoru woman’s lens on how we understand our migration.”

On the larger topic of migration she said that it’s a natural progression for human beings to migrate and to move but the reasons CHamorus relocate “are so complex.”

When people are thinking of leaving the island they think it’s not necessarily for forever, she said. “Whenever I would talk to my grandpa his dream was to always go back to Guam and to bring the whole family back”.

Over the last half century the ebbs and flow of CHamoru migration attributed to U.S. military influence and educational and career opportunities commingled over a period of time to where we are today — that there are more people of CHamoru bloodlines living in the U.S. and abroad than there are living on the island of Guam.

“There are multiple reasons why people migrate, multiple reasons why people don’t go back and what keeps people here,” she said. “But I think there is always that longing to go back. I talk to so many CHamorus, whether they are family members or non-family members, and everybody wants to go back — so there is a question of why we don’t go back, and there are really deep reasons for that.”

Tough questions

The personal reasons for staying, the external resentment and self-inflicted guilt of those with CHamoru bloodlines, stateside and worldwide, may be as “tadong” as the Pacific Ocean that separates us from the home island.

“I think there are CHamorus in Guam, (saying) that if you are so mahalang to come back home, then why don’t you come,” Arroyo said. “We are judged for staying here and I understand that feeling because I think it’s a feeling of betrayal almost.”

“Why are there so many CHamorus in the states and why don’t you come back home — it’s a hot topic,” she added. She is not alone in answering these tough questions. According to Arroyo, the surge of global indigenous movements has spawned young CHamoru scholars and activists here and on Guam who are exploring and scrutinizing among other things the CHamoru identity.

At the Hayward Catholic cemetery I easily spot Chamoru names on gravestone markers. Arroyo points to those of Frank Balajadia Manibusan and Brígida San Nicolas Duenas, her maternal grandparents who helped raise her and her sister.

“It’s their daily stories remembering how things were. Maybe my grandfather would mention something or my grandmother when she was cooking or cleaning would say a sentence or two about something that she remembered about being back home. To me it’s a collection of stories of how I understand CHamoru culture and how I’ve been able to pass what’s really important to us down to my kids,” Arroyo said.

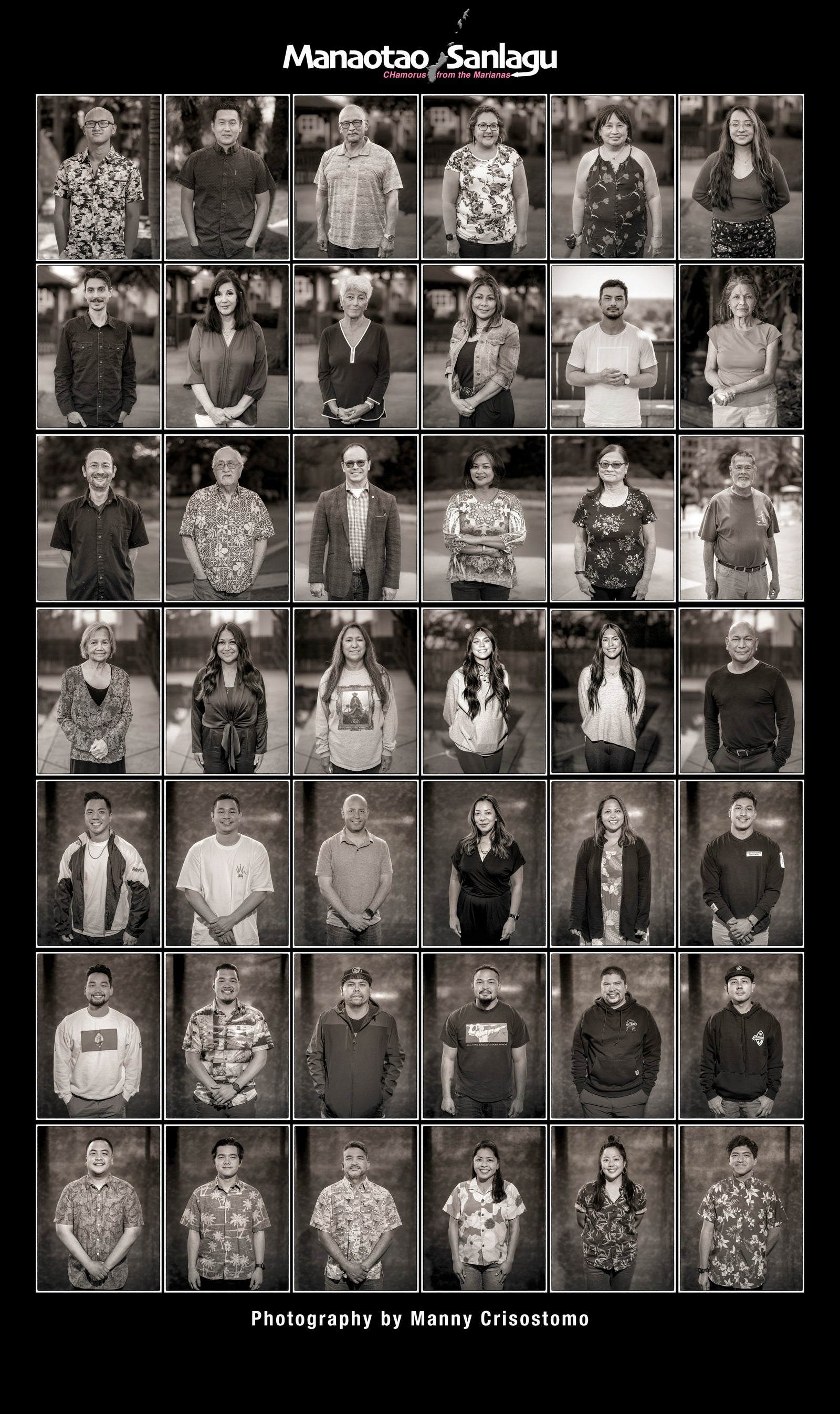

Manaotao Sanlagu is Manny Crisostomo’s ongoing visual documentary of CHamorus from the Marianas living overseas that is featured weekly in the PDN. If you or someone you know would like to be part of this documentary or wish to support this project, contact Crisostomo at sanlagu.com. The project is sponsored in part by Brand Marinade, a CHamoru-owned creative agency in the San Francisco Bay Area.