By Manny Crisostomo

Over a decade ago, Mario Reyes Borja and San Diego area CHamorus, many in their 60s, used scaling data and traditional and modern handheld tools to bring a 1742 drawing of an ancient CHamoru flying proa into reality in a makeshift canoe house in a Southern California backyard.

A 47-foot single-hull, single-outrigger CHamoru sakman carved from a large California redwood tree was completed in 2011 and christened “CHe'lu.” Three years later the 5,600-pound sakman — the largest class of CHamoru canoe — was in Guam waters with over a dozen traditional island canoes that triumphantly sailed into the Hagåtña marina to open the 12th Festival of Pacific Arts in 2016.

“We were happy to be out there and to be celebrating the union of canoes, every sail pointing into the sky meant that we had one purpose — to catch that wind. Our bows were all pointed into the channel, that meant we had one direction,” Borja recalled. “We were fugu, we were tearful. I was proud to be there, I was proud to be a CHamoru and proud to be a seafarer. I wanted my ancestors to be proud of what we had done.”

That seminal moment has stayed with Borja, and his passion for all things canoe remains unabated. He is taking that same 280-year-old British naval archives drawing, titled ”’A Flying Proa,” and updating it with artificial intelligence, 3D renderings, and holographic, virtual and augmented reality applications.

“We’re taking the canoe’s front, side and top views and we’re adding five more views,” he said. “We want to look at it from a 180-degree isometric perspective and also from a 360-degree perspective. Looking at the very structure of the canoe, how the curves meet up, and how the hidden lines become exposed. We want to look at every little component and how things were jointed; we want to explore that because all these little bits of data that are important to the survivability of the construction of the canoe are missing.

“From there, we’re going to study the canoe and the sail from a different perspective via a wind tunnel,” he added. “We’re going to do 3D printing of the canoe, (then) building small handheld canoe models — three foot or even an eight foot … — that we can use to teach children.”

Beyond 3D models for hands-on learning, Borja has to launch an analog and digital canoe building and seafaring culture to anyone who is interested.

“We want to take it from the embryonic stage to the sailing stage. We have several phases,” he said. “The fañagu stage is to learn the canoe, learn the history, learn the mathematics, and then the hátsa stage, that’s when you start putting the canoe together. And then you get the layak stage where people learn how to sail the canoe. And then the last stage is up to the person to define the ownership stage.”

Simulated sailing

He is excited about working with folks like Vince Diaz and his contemporaries at the University of Minnesota. Diaz is founder and director of The Native Canoe Program, housed in the Department of American Indian Studies at the university.

“We talked about how people can actually simulate experience on the canoe by virtually holding a lever being the steering paddle and the rope being the sheet for trimming the sail,” he said.

“By holding on to that, you have a tactile sense of components on the canoe. Virtual reality puts you in the ocean on top of a canoe. And how you pull that rope is the behavior of the sail follows (and) how you pull on that steering paddle, the behavior of the canoe follows.”

From analog traditional canoe building using tools of old — the adze and the higam — to digital computational computing to augmented and virtual reality, the CHamoru flying proa and seafaring is continuing its renaissance with Borja’s determination.

The mathematical and technological challenges don’t faze the 73-year-old retired Air Force captain, who has a bachelor’s degree in aerospace engineering from the University of Texas at Austin, a master’s in astrodynamics at the Air Force Institute of Technology, and another master’s in engineering management from the University of Southern California. He also got his math teaching credentials from San Diego State University.

“I am sitting here at home writing up all the math that is embedded in the sakman and I am getting overwhelmed with admiration and respect for our ancestors who built the proa centuries ago,” he said. “They may not know the scientific terms to describe the phenomenon the proa is, but they understood fully well the utility of the product of their hands.”

Saipan, Guam roots

Mario Reyes Borja was born in Chalan Kanoa, Saipan, to Joaquin Flores Borja, familian Bodoki of Tamuning, and Magdalena Reyes Borja of Saipan, familian Toliok. He and his twin brother, Tony, are the third and fourth oldest of 12 siblings. The family moved to Guam when he was 4 months old.

He remembers as a young boy building galaides made with tin roofing sheets with his father and his seven brothers.

“Growing up, we make them and we take them out to Ypao,” he said. ”We play with them, embellish them and form outriggers. We even tied two small canoes together for stability. That’s the extent of our seafaring days, something small to play with, or fish from something to enjoy as a child.”

After graduating from Father Duenas Memorial School in 1967, he enlisted in the Air Force where he did avionics maintenance and was a senior systems analyst in the space surveillance field before he retired after 23 years of service. He later moved to San Diego to care for his mother until she passed away in 2003.

He also retired as a math teacher in middle and high schools in San Diego Unified School district and now works as a CHamoru interpreter in the federal court system.

He is a founding member and senior cultural advisor for the Chamorro Hands in Education Links Unity (CHe’lu), a nonprofit based in San Diego. The group sponsored his Sakman Chamorro Project and raised $30,000 cash and in-kind donations to build and ship the sakman to Guam.

Source of inspiration

He and JoJo, his wife of 50 years, are active in the CHe’lu organization and Sons & Daughters of Guam Club in San Diego. She has supported his passion for canoe building and seafaring traditions since 1995, when the Hokule’a, Hawaii’s famous voyaging canoe, built in the double-hulled style used by Polynesian navigators thousands of years ago made a stop in San Diego.

“This canoe came in, and it inspired me, in a very aggressive way, to inquire about our history. What happened to our canoes? I was angry. What happened and how come we’re so ignorant of our history?” he said.

He got his history lessons and inspiration from Carlos Pangelinan Taitano, one of the fathers of the Organic Act of Guam and a champion of CHamoru rights and indigenous culture, who had moved to Los Angeles. Taitano provided him with the 1742 flying proa drawing and asked him to build it.

3 instructions

“He gave me three instructions,” Borja said. “He said, ‘Na lailai i taotao tano; let live the people of the land. Hatsa i sakman; build the sakman. Hagu i kannai mami; you are our hands.’ Then he added this fourth line, which is not really an instruction, he said, ‘Ai i mohon i tempo ku; if only in my lifetime.’”

Taitano told him two and half centuries have lapsed since the last known documentation of CHamoru sakman sailing the waters off the Marianas Islands, and that motivated Borja. “God, dang it, I’m going to do it,” he said. “I’m the son of a carpenter and a fisherman, I’ll do it. My elders jumped in with blind faith in pursuing this canoe project.”

‘Just the first edition’

His sister, Linda Rose Goldkamp, offered her El Cajon lot for the construction of the sakman.

On the islands, dokdok or lemai trees were traditionally used. In California, the diaspora CHamoru canoe builders used a redwood tree from National Sequoia Forest in Mendocino.

“When we began our project, there were eight of us at the yard. Several more joined our project once they saw the hull hewn out and the bows in place,” Borja recalled. “I worked eight hours per day on it, and my crew joined me during weekends and later went full time every day until completion. There were then 16 of us, the eldest was 95, youngest 2, many in their 60s, a few older.”

Sadly, Taitano died in 2009, two years before the sakman was completed.

“We are not canoe builders. But we have the determination to build a canoe,” Borja said. “This is just the first edition, and second edition and third edition and all the other editions that will come up. We’re going to perfect it, we’re not scared of that challenge.”

Racing challenge

Speaking of challenges, Borja said canoe builders from the Marshall Islands have challenged his crew in a race. He is rounding up the same crew of carvers who built CH’elu and training a new crop of young kids to build a racing canoe by 2024 using contemporary materials but preserving the traditional design.

“We had a time to relax, and look at what was done, but we’re not resting on our laurels,” he said. “We’re going to build it so that the kids can be part of this. We’re going to challenge ourselves and be competitive.

“I always contend that if you want to learn more about the culture and language of an island, look at its canoes,” he said. “It will tell you about the origin and the survival of the people.

And I feel that to be the truth. So we’ve got to start there.”

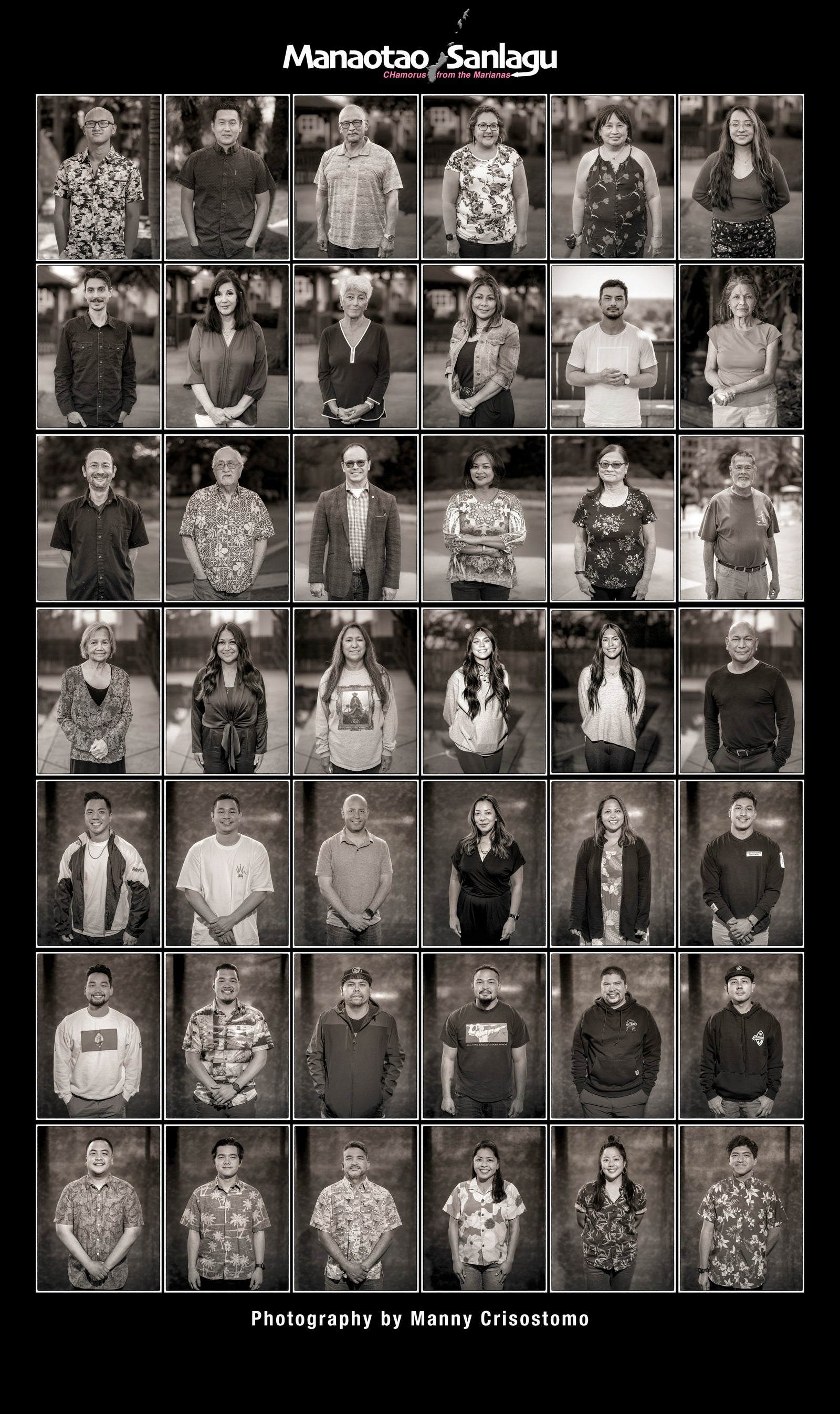

“Manaotao Sanlagu” is Manny Crisostomo’s ongoing visual documentary of CHamorus from the Marianas living overseas that is featured weekly in the PDN. If you or someone you know would like to be part of this documentary or wish to support this project, contact Crisostomo at sanlagu.com. The project is sponsored in part by Brand Marinade, a CHamoru-owned creative agency in the San Francisco Bay Area.