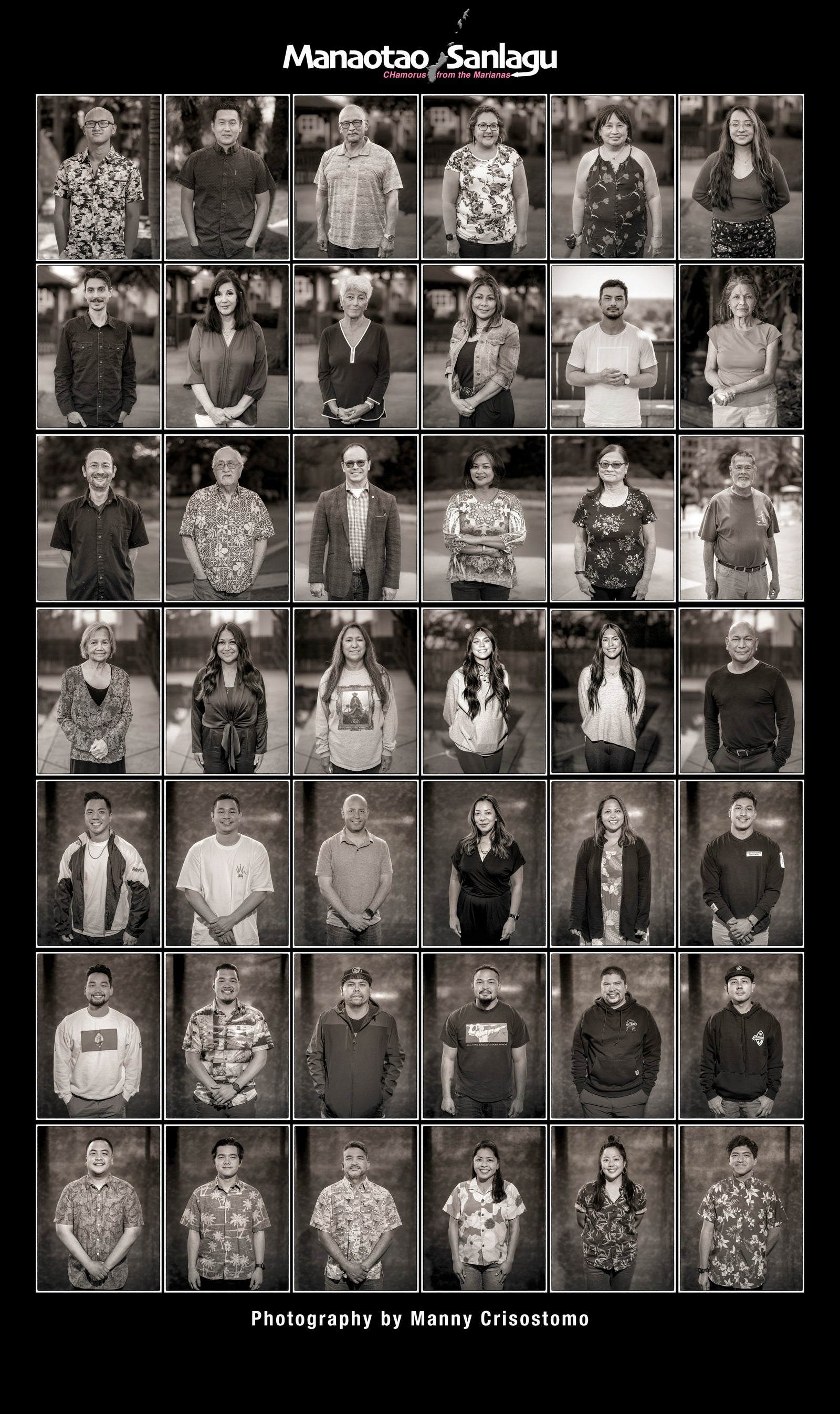

By Manny Crisostomo

When he was 15, Adriano Birosel Pangelinan came home one day with an abstract acrylic portrait he painted in his art class at George Washington High School.

“I really liked it, I got some nice compliments about it, even my teacher, Mr. (Anthony) Anderson really liked it and he knew my dad. But my parents didn’t say a darn thing,” Pangelinan recalled.

This would have been traumatic for most teens but more so for Pangelinan, whose mother is an artist and his father is one of the most accomplished and prolific CHamoru painters on Guam.

“I felt bad about it and later on, my mom said, ‘We didn’t want to encourage you,’” Pangelinan said.

“My parents had to work hard and struggle to keep the family safe and fed, and housed. I’m guessing that my parents just didn’t want to see me go through that too. And I think she knew that I had a future in sort of, you know, engineering or science.”

His mother turned out to be prescient, as the now 58-year-old Pangelinan had a successful career as a chemical engineer with a doctorate and several process patents during his 27 years at Shell Oil Co. in Texas before retiring.

He then joined the health care field as owner and operator of several high-revenue urgent care facilities in the Houston area.

His father’s legacy

Adriano Birosel Pangelinan is the second oldest of four born to Adriano Baza Pangelinan, familian Mali, of Tumon and Patricia Birosel of the Ilocos region of the Philippines.

“She and my dad met, while they were both art students at the University of the Philippines, in Manila,” he said.

His father, Adriano Baza Pangelinan is “considered one of Guam’s pioneers in contemporary painters who began his prolific art career in the late 1960s when he was a student at George Washington High School,” according to Guampedia.

“Barely 17, he was invited to participate in the Chautauqua Institute Art Exhibit in New York State. His watercolors immediately garnered media attention, and an article about him appeared in the New York Times. A year later he was invited to exhibit his work in a one-man show at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.”

After graduating from Southern Illinois University with a Master of Fine Arts degree in painting in 1973, he returned to Guam and taught at the University of Guam until his retirement in 1993.

The younger Pangelinan knew from a young age that his dad was a big deal.

“Oh, I knew that since I was a little kid. I knew he was very talented, and respected,” he said.

“I’m still very proud of my dad and we’d see his work all over the place. I’m proud to tell my kids about it. So it’s something that my kids are proud about, too.”

But it was also his father’s work ethic and commitment to family that inspires him to this day.

“My dad taught me a lot,” he said. “He was such a hard worker, always working hard for the family. I’d helped him build the houses that we lived in. He was very independent, very resourceful, very industrious. And that had a big impact on me.”

Becoming an engineer

Growing up, the younger Pangelinan thought himself “kind of the black sheep of the family” for being interested in things “technical,” including math and chemistry, and for joining the military.

He graduated from George Washington early and went to UOG for a couple of years to “mature up a little bit,” then joined ROTC and the Army Reserve for structure.

“Even though my dad was very hardworking, I grew up in an artist family, where I pretty much did what I wanted to do, and you know, I didn’t have that much discipline,” he said.

He left UOG after his sophomore year.

“I transferred to the University of Washington and decided chemical engineers make a lot more money than chemists. So I decided to become a chemical engineer,” he said.

“I really liked it so that’s when I decided to get a Phd.”

With his good grades, he was able to get into University of Delaware in Newark, Delaware.

“It has one of the top programs in the nation and that’s where a lot of chemical companies started, in that Delaware Valley area,” he said. “I went there, specialized in plastics and I got my Ph.D in 1991.”

His commission with the Army Reserve and the reserve’s Simultaneous Membership Program provided tuition assistance throughout his college years. He didn’t see the military as a career and opted to let his obligation end as first lieutenant.

Working for Shell

Shell offered him a job a year before he graduated at University of Delaware but he wanted to see what was available on Guam.

“As soon as I graduated, I went to Guam for a month. But there weren’t any chemistry or math positions available at the time,” he said.

“If there was a teaching position at UOG, I would have done it, it would have been a lot less pay. I miss home and I’d like to teach and I would have enjoyed that. But there just wasn’t anything.”

So he moved to Texas and took the job with Shell in Houston. “I was very much a researcher, the first half of my career. I helped develop new products, one that’s very successful that has several patents in it,” he said of Corterra PTT, a new fiber for the carpet and textiles industry.

The carpet industry promotes carpets made with Corterra fibers as being stain resistant and durable.

He later moved into management and held a number of high profile technical management or marketing positions and after nearly three decades he retired from Shell in 2017.

Business after retirement

But he wasn’t ready to sit around collecting a pension or going on cruises, as he and his second wife have a young daughter.

So he and his wife, Solherney, who was a physician in Venezuela, began looking into starting a business.

They looked at being a Chick-fil-A franchisee and even considered a crime scene cleanup business, which tends to be lucrative.

“I had been with Shell for 27 years, so I had the means and resources to start something and we eventually focused on urgent care.”

In April 2019 they opened Urgent Care Center in Richmond, Texas, 15 minutes from their home. “She runs the clinic, and I do the financing, the construction and all that sort of stuff. But in terms of hiring, firing and all that, it’s all her. She does the day to day and she loves it,” he said.

“What urgent care handles is everything up to lacerations, simple broken bones, STDs, all sorts of the vast majority of things people would consider are emergencies but aren’t really emergencies and you don’t need to go to a hospital or even a primary clinic.”

“It’s pretty successful and we’re starting another one in about three months and plan for a third one, and we’ll probably call it quits right around five or six years,” he added.

“Sell those businesses off unless someone in the family is interested in running it. And you know, just truly retire when my daughter is done with high school.”

I asked him if he thought of opening an urgent care clinic on Guam and he said his operation is too small to be spread out that far apart. “I don’t know, if I have the energy and the resources to handle it, you know that span.”

Dreams of teaching

“One of the dreams I had was to teach at UOG. I’d love to help kids with math and engineering, and now there is an engineering school in the University of Guam. If I figure out a way to do that, given my family constraints and the business constraints, I would love to live in, you know, at least half time in Guam.”

“I always wanted to be in a technical area, I knew that, and so I lived the dream of that, to be an engineer at a very high level to invent things and to lead teams. I did what I wanted to do and I’ve enjoyed my career.”

I asked him if he had any regrets about not being an artist like his parents.

“It was only later on when I was an adult that my mom saw that picture and said, ‘Oh I really liked it,’ and I said, ‘Mom, you didn’t tell me that?’”

“And then she said ‘Oh, yeah, that’s right, we didn’t want to encourage you,’ and I was surprised,” he recalled. “ I was 28 and I already had my Ph.D. I was old enough that we laughed about it.”