Jeremy and Jay Castro were born and raised surrounded by i kustumbren CHamoru in their Victorian style home in Alameda and in the neighboring houses along Pacific Avenue where the Castro, Manibusan, San Nicolas and Duenas families lived in in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Growing up, their family gathered every Sunday at Nåna and Tåta’s house, and every year since the 1960s their extended CHamoru families along Pacific Avenue would hold Guam style fiestas, cooking Guam foods, sharing updates about family back home, and telling stories of CHamoru life back on the islands.

Growing up the brothers would wear their culture on shirts, caps, stickers on their cars, and gold Guam seal necklaces that relatives would bring from the island around their necks.

They would watch their grandparents, their dad, aunties and uncles making the red rice, titiyas, kelaguen and barbecuing the meats.

They worked and pitched in like everyone else during the big parties, they learned at an early age respect for elders and to mannginge’, and although they didn’t quite understand it then, they participated in the CHamoru cultural dynamics of inafa’maolek and chenchule’.

But the brothers had a gnawing sense that there was more to who they are. A deeper form of mahalang — for they weren’t longing for the home island they left. They were searching for a connection to an ancestral place that they had never been to.

Setting roots

Their Tåta and Nåna were Jose Rosario Castro, familian Piyu’, and Rosalia Garcia Cruz, familian Jeje, both from Hagatña. Jose Rosario Castro, who was in the Navy, was reassigned in 1952 to the West Coast and the family left Guam aboard the U.S. Naval Ship General Edwin D. Patrick.

Jeremy and Jay’s father, Joe Castro, was 4 years old when he boarded that ship with his parents and siblings. The family eventually set roots in Alameda.

Joe Castro, who is the second oldest of his six siblings, married Janet Ann Fasso, a second-generation Italian from New York, in 1974 and had the two boys.

“It’s amazing it took this next generation, the first generation born here, to grab a hold of the culture so strongly,” said Joe Castro, 72, a retired licensed land surveyor from Alameda. “I just assumed my heritage, whereas as these guys, they pursued it.”

Jeremy Castro, 44, is an entrepreneur and “chief catalyst” of a large-scale screen printing, eCommerce business and a creative agency in the Bay Area called Brand Marinade, inspired by the CHamoru fina’denne’. (Brand Marinade is also a sponsor of the Manaotao Sanlagu visual documentary.)

Jeremy Castro was 11 when he hung around with Nåna and Tåta. “I will always find a way to hang out with Nåna, because she will feed me when she was cooking but you will only get fed if you were helping so I will learn how to wash dishes,” he said. “I will be spending time with them, laughing, cooking, washing dishes, pulling weeds in the garden, and catching chickens in the yard.”

Although his grandparents had a trove of CHamoru stories, he never got to hear them because he didn’t understand CHamoru and his grandparents didn’t speak much English. “I didn’t get to hear much of the stories, that was one of the things missing for me.”

Epiphany

An epiphany came when he was 14 years old and his father gave him “Homeland, 1992,” a CD by Jesse Manibusan, who lived nearby.

“Once I heard that album I was like, oh man, that was what I was searching for. His song ‘Forever Chamoru’ was poetic. I would look at the album cover and it’s Uncle Jesse, I knew him my whole life, he looks like my dad. There is this element of CHamoru I started to understand a little more and that there is more of us than just my family. That album gave me the first glimpse into the fact that there was much more and worth spending the rest of my life trying to understand.”

Jeremy Castro would play the CD continuously in the bedroom he shared with his brother, Jay, who was seven years younger than him. Jeremy would pore over the album art and the lyrics and liner notes. He was flabbergasted when I told him I flew from Guam to Alameda three decades earlier to photograph Jesse Manibusan for the album cover.

He recounted the lyrics, “grew up pretending I was nothing more than than the boy next door, your average American guy,” from the “Forever Chamoru” song.

“That’s the way most CHamoru boys grew up in the U.S., we were just like regular as anybody else as far as I knew,” Jeremy Castro said. “For the first time in my life I got introduced to this idea that our culture was so much bigger than I understood. Because what I understood Chamoru culture was – being at my grandparents house eating red rice, titiyas and making kelaguen, at gatherings going to each person saying hello and saying goodby and mangingeing all the elders.”

“That album gave me the first glimpse into the fact that there was much more …spending the rest of my life trying to understand,” he added.

Jay Castro, 37, started his tech career as a partnerships manager at Wildfire Interactive, who was later acquired by Google.

He then became a UX content strategist while at Google, at Airbnb, and now at DoorDash. While at Airbnb and now at DoorDash, he leads their Native American and Indigenous peoples employee resource groups and advocates for Indigenous inclusions in all aspects of the business.

Wearing culture

Growing up in Alameda, he literally wore his culture on his sleeve.

“We wear it all over our shirts, wear it on my hats, I used to have the Guam seal stickers on my cars, I will try to say and blast out loud I am from Guam, my family is from Guam, we are Guamanians – I didn’t know CHamoru till I got to college – I didn’t even know that word existed,” he said.

“I did all these things to be proud outwardly, but really on the inside I felt quite empty,” he said.

Not satisfied with the few books on Guam history he read and the family stories of the island, Jay Castro said he had to do a lot soul searching and culture searching on his own.

“First five to six years of me searching for my culture and trying to understand my identity, Guampedia was like my Nåna – I will ask a question to the internet and Guampedia will give me back some answer that will make sense for me,” he said.

At the suggestion of his wife, Katherine, he filled out a form on the Guampedia website.

“I wrote, ‘Hey my name is Jay Castro from the Jeje, Piyu family and also kinda San Nicolas Kimudu family and I work at Google. I love your website, it’s given me so much inspiration, it’s helped me understand these values I grew up with and put words behind them so I can understand them and articulate them better .. how can I help you? I am not asking for any money, I want to help because I want to be more connected to the island.’”

It didn’t take long for Guampedia managing director Rita Pangelinan Nauta to reply that she was grateful for feedback on the site and content and that they were reaching CHamorus.

“I was also struck by his wanting to support our efforts in the preservation and perpetuation of our unique history and rich CHamoru/Chamorro heritage of the Marianas, especially for someone who has never even been to the islands,” Nauta said.

Jay Castro says he has helped fixed the search option on their site, helped create mobile-first websites to make their content available on phones, worked on a research project to better understand the diaspora and help diversify their revenue stream, and find new and sustainable ways to grow the business so they can become less reliant on government grants and donations.

In turn, he said Guampedia gave him a feeling of being culturally connected and welcomed.

“Beside my blood and my close family, I never really felt very CHamoru, I didn’t know what it was to be CHamoru,” he said. “By meeting Rita (Nauta), Shannon (Murphy) and Nathalie (Pereda) and the whole team that is there, I felt it. I knew what it was because I had it when I spoke to them, I had it when I got to work with them, I had it when I read their content.”

Growing business

While his younger brother was doing his Guampedia work pro bono, Jeremy Castro was growing his business in the highly competitive apparel industry borne from the work ethic he learned from Tåta and Nåna.

Brand Marinade has a stellar list of clients that include NFL player Marshawn Lynch’s Beast Mode, Bleacher Report NBA, NBPA (NBA Players Association), NFLPA, Ruff Ryders, Roland, The Compound, Juniper Networks, Nintendo, Pandora, National Geographic, Tiger Balm, Pixar and Zion I.

Aside from those national brands, they also support marginalized communities, such as Glide Memorial Church, East Oakland Collective, Healthright360, San Francisco Department of Public Health, Compassion in Oakland, Fam1st Foundation (Lynch’s nonprofit), DoorDash Natives in Tech, and indigenous employee resource groups at Airbnb.

Over the last few years his company gave away over 120,000 masks, distributed 32,000 pounds of free fresh produce to local families, and donated 4,000 social justice shirts to local organizations during the George Floyd protests.

Jeremy Castro is equally proud of building a company that provides full-time jobs in an environment where each person is supporting the other’s individual goals and needs — inafa’maolek in the workplace.

“All I am doing is replicating how I was taught growing up. What we do every time we have a big family party, it might be 20 or a hundred, either way you manage it the same way: By treating everybody nice, making sure people have what they need, giving people things that make them feel good, talking, catching up getting to know what is going on (in their lives), taking a personal interest, and being considerate,” he said. “I am trying to have everybody have the same goal — you know like inafa maolek. That is the nature of what we do in daily basis.”

But no quest and search for one’s CHamoru-ness is complete without a pilgrimage to the ancestral home.

Reconnecting

After decades of talking about going to Guam, Jay Castro organized a Guam trip with his parents, his brother and his girlfriend, his wife and young son and cousins — 13 in all. They landed on island in July 2018, a long-overdue trip to visit friends they made virtually and relatives they had never met.

“We never really looked at going to Guam as a vacation, we always looked at it as reconnection,” Jay Castro said. “We talked about going to Guam because we wanted to eat the food, to meet family, ‘cause we wanted to drive around the island. My dad wanted to reconnect, to go back to the villages he used to live in.”

The Castro clan stayed at a large beachside Malesso rental for 30 days.

“Neighbors found out that we were there, found out that my dad was born there and that he brought his whole family,” Jay Castro said. “And we were getting little gifts the whole time we were there, something new on our doorstep, fresh fish, dried fish, kelaguen, red rice and gifts.”

During their time on island the brothers would spend hours at the Hagåtña library reading books and manuscripts only available there, and at the University of Guam’s Micronesian Area Research Center, getting more information on their family lineage. Their dad, an avid commuter cyclist, was riding his bike everywhere.

For Jeremy and Jay Castro, one of the highlights was a visit to an ancient latte site in Manenggon organized by Rita Nauta and led by Nauta’s uncle, Joe Cruz.

The group hiked for 45 minutes through the dense halom tano and when they got to the ancient latte site, they helped clear jungle debris, weeding around the leaning haligi and the fallen tasa lying next to it.

Jay Castro was humbled by this physical connection to the land and the spirit.

“Something took over me, I was the most quiet I think that I have ever been, I just didn’t have words, (my wife) Katherine was worried for me, asking me why aren’t you speaking. I was speechless just listening to Rita and her uncle tell stories.”

Jeremy Castro had fallen behind the group, as he would occasionally stop to take pictures, just absorbing the quiet of the site and the halom tano.

“We were presented with something so deeply educational in experience and understanding (that) we didn’t need to say anything because it was just all there, it was everywhere around us,” he said. “And I just kept thinking what was like there a couple hundred years ago, a couple thousand years ago.”

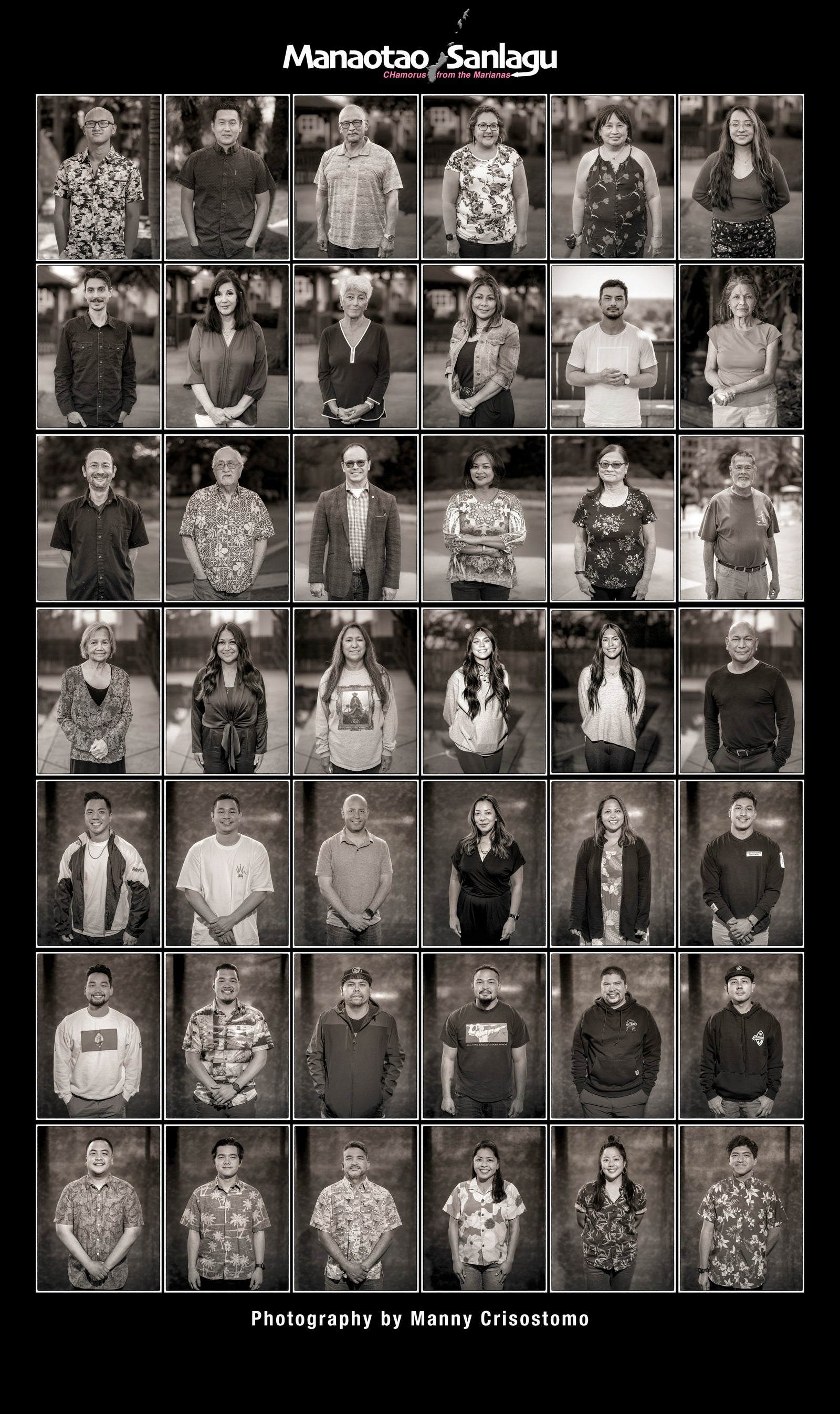

Manaotao Sanlagu is Manny Crisostomo’s ongoing visual documentary of CHamorus from the Marianas living overseas that is featured weekly in the PDN. If you or someone you know would like to be part of this documentary or wish to support this project, contact Crisostomo atsanlagu.com. The project is sponsored in part by Brand Marinade, a CHamoru-owned creative agency in the San Francisco Bay Area.