By Manny Crisostomo

Fran Nededog Lujan has been designing and creating since she was little girl growing up in Agana Heights. “The creativity part — that is already wired in me,” she said. “I have always been like that, I don’t know what it’s not like to make things look pretty.”

She also spent most of her adulthood, filled with struggles, setbacks, sorrow and grief, designing a life that revere her family and her passion — through her expertise in the arts — for Oceania traditions that perpetuates Pacific cultures.

“Job one is to be mother that is always job one,” says the 58-year-old Lujan, who is quick to add that she also takes her role as nåna to her two grandkids seriously.

“Job two is to perpetuate our culture not just CHamoru culture, but also the cultures of Pacific Islanders, Oceania indigenous people,” says Lujan who heads the Pacific Island Ethnic Art Museum in Long Beach, California. “And the only way I know how to do job two is through the world of art, it is only through that vehicle, it is only through that medium.”

Fran Lujan is the middle child of five children born to Concepcion Sablan Nededog, familian Nededog, from Agat and Frank Flores Lujan, familia Bittot, from Agana Heights.

While at the Academy of Our Lady High School in Hagåtña she was editor of the school’s Checkerboard newspaper and recalls “they will pull me out of class to go decorate the altar and design the stations of the cross banners.”

She left Guam to pursue a journalism degree at Seattle University. “Writing and design to me they are always connected. If you are going to read a book I need to make it beautiful,” she said. She returned home to work at University of Guam, College of Agriculture & Life Sciences designing, writing and producing educational publications including designing the first Hale’-ta series of books by Dr. Katherine Agoun.

Divorced and a single mother to then 3-year old Taylor Elizabeth Torres she decided to leave Guam in the summer of 1993 to get a master’s at Cal State Fullerton.

“I already had family members who lived out here and the goal was to finish (a master’s degree) and go back home,” she said. “But unfortunately my choice to continue being out here was both my mom and dad end up relocating to Long Beach for health reasons and I stayed to be with them.”

After grad school she worked at several technology companies using her visual and graphic design skills in corporate communications and company branding. But she wanted to be a mom and worked with her second husband, John Henrich, so she could have both the mom experience and her creativity work.

“I left Mitsubishi (Electric America) when Taylor was in third grade and I stop working full time until Taylor graduated from high school because the job was to be a mom that was the focus,” she said. “My husband knew the priority is to be a mom and to figure out how to live on one income and a gig income. I am a total gig person.”

As a freelancer or contract graphic designer she has created numerous marketing collateral, logos, brochures, annual reports, booklets and posters for her clients.

She is especially proud of her work with Asian American and Pacific Islanders nonprofit organizations and other marginalized communities in Southern California designing and developing bilingual health education material in 16 different languages including CHamoru.

“I kept thinking if my mom got a brochure in CHamoru that talked about her own health care I bet she would have read it and would have understood it much more,” Fran Lujan said.

Doting on family

She and her second husband tried to have children but weren’t successful.

“John and I would have love to have kids but when we were the process I realized I could not have any (children). We have gone through these struggles,” she said. “I was really lucky to have Taylor, she is my miracle.”

Nowadays she is a doting grandmother to Taylor’s two children, 9-year-old Hayden Parker and 2-year-old Layla Parker, whom she watches several times a week.

“I am still here ‘cause now I am a nåna and that is really one my deepest purpose in life is to be present for my grandchildren as much as I can,” she said. “So I chose to stay in California for them.”

It’s been 28 years since Fran Lujan left Guam for grad school and to be in Long Beach with her other siblings to care for their parents, who had chronic illness.

The day after Christmas in 1996, her mother, Concepcion, succumbed from uterine cancer at age 63. On Christmas Eve 2009 her father, Frank, died from a heart attack and two months later, her younger sister Tina Lujan Sanchez died from a rare form of bone cancer.

‘I live my legacy’

And in between the deaths of parents, she was diagnosed with a pituitary adenoma in her brain.

“I have a little tumor in my brain. It’s a tiny, super tiny but knowing that is why I live my life the way I do,” she said. “I live my own truth and my own purpose with the resources and the abilities that I have been given. I live my legacy now, I don’t want be remembered I want to live my legacy today because we don’t know what tomorrow is going to be.”

She joined PIEAM, the only museum dedicated to the Pacific Islands in the continental U.S., when it first opened in 2013 doing community outreach and coordinating exhibits for four years before leaving to work in the artistic gig community.

“I rejoined back in 2019 to become its first Pacific Islander CHamoru native museum director and curator,” she said. “I am nurturing work, that couldn’t happen in my 20s, 30s or nor my 40s. I really had to get to a certain age group and I had to do the work to earn the respect of the community out here.”

‘Rooted in Guåhan’

She sees the CHamoru identity struggles that diaspora artists have and helps them channel that angst.

“It is my journey to help, help them to find that truth, in the best way that I can, which is through the way of the arts. Our artists, the work they do, is breathtaking and it’s really a way our diaspora can connect with where they are from”.

She added it’s been a challenge understanding the anxiety of CHamoru artists who grew up stateside.

“I am rooted in Guåhan. I am very confidant of who I am and all the cultural values that were gifted to me because I was raised in Guam,” said.

“I listen more carefully to who they are, what they are trying to build, what brings them joy and what makes them sad. And I see if they are walking the CHamoru way and if everything they do is inafa’maolek, even though they may not know what the word means.”

‘Unique kinship’

Lujan’s affinity for CHamoru culture and traditions is understandable but the museum’s mission is “inclusive of all our cousins of the Pacific Islands,” she said. “This includes working working with artists of Pacific island lineages, Samoans, Māori, Kānaka Maoli, Tongan, Belauans and artists from FSM.

“We recognize the unique kinship that exist between objects, people and their histories and the obligation that comes with this recognition.”

Lujan is still crafting and designing her legacy in real time, in the present, despite all the struggles and the losses she’s endured.

Family remains her priority as she quietly brings i kustumbren CHamoru to the California homes of her daughter, grandchildren and remaining siblings.

And she has a sense of urgency harnessing the nurturing and caring power of inafa’maolek within the walls and grounds of the museum, launching a beacon to diasporic CHamoru artists and their oceanic brothers and sisters artist searching for identity in the healing and reaffirming power of art.

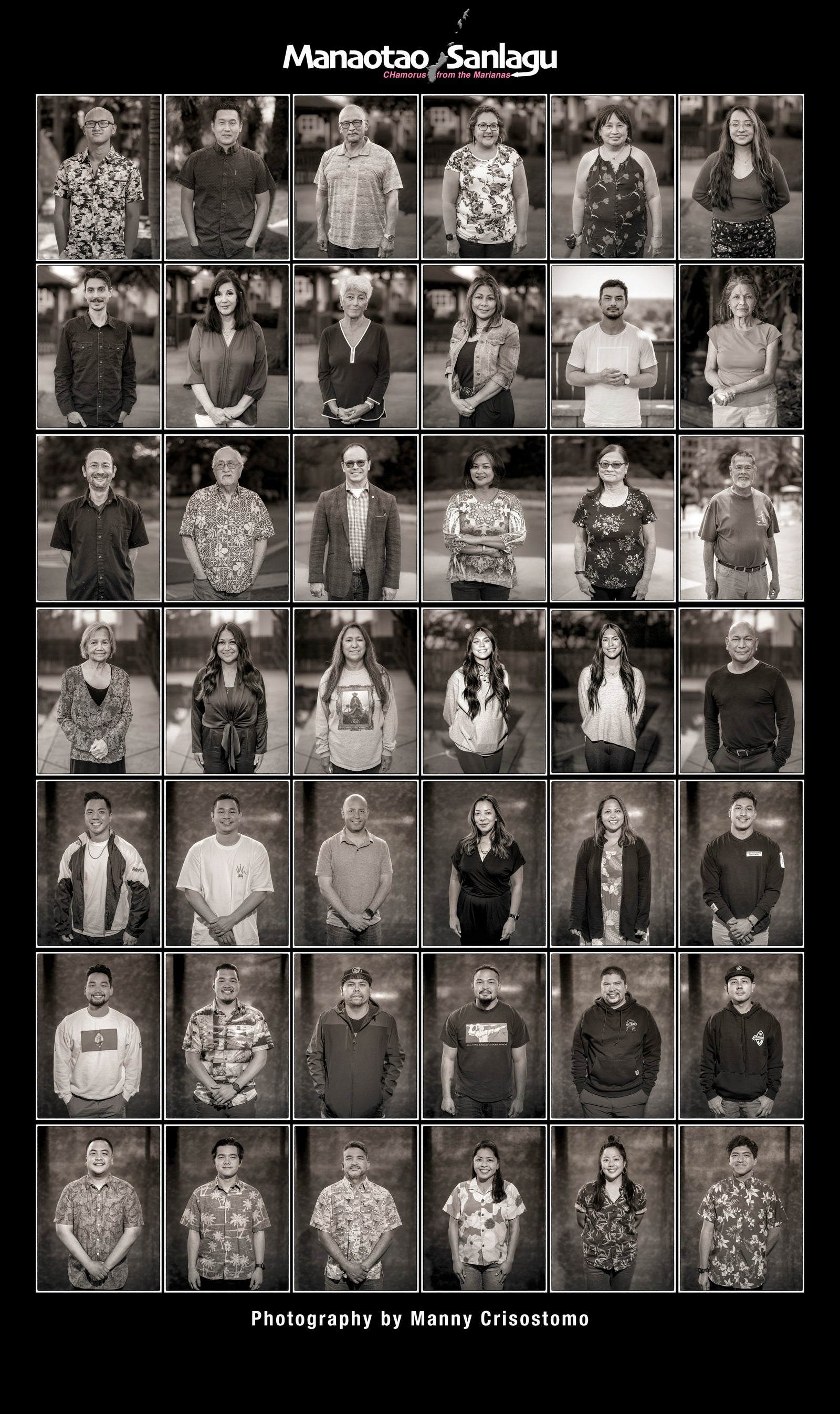

Manaotao Sanlagu is Manny Crisostomo’s ongoing visual documentary of CHamorus from the Marianas living overseas that is featured weekly in the PDN. If you or someone you know would like to be part of this documentary or wish to support this project, contact Crisostomo atsanlagu.com. The project is sponsored in part by Brand Marinade, a CHamoru-owned creative agency in the San Francisco Bay Area.