By Manny Crisostomo

Mary Therese Perez Hattori is a multifaceted individual, a modern-day Renaissance woman with an array of professional credentials and expertise across disciplines and an equally prolific set of passions and interests.

In addition to being an author, poet, public speaker, philanthropist, community organizer and advocate, she is also a researcher and teacher with a background in technology and telecommunication, computer coding, and database design — as well as a doctorate in culturally responsive educational leadership and indigenous research methodologies.

“I can tap into all of my interests and all of my strengths and work across disciplines and across units,” Hattori said of her job as interim director of the Pacific Islands Development Program at the East West Center in Hawaii.

There, she leads a staff tasked with addressing racism, discrimination, economic inequality, digital divide, climate change and the coronavirus pandemic’s impact on health and the economy in the Pacific region.

They also initiate a broad range of programs to showcase and enhance the quality of life in the Pacific Islands.

But, as Hattori will explain, her diverse list of credentials and accomplishments is not unique but an inherent quality of her brothers and sisters in Oceania.

“It really reflects Pacific Islanders and our way of being. We don’t silo ourselves. It’s not unusual that a master weaver might also be a great songwriter or singer,” she said.

“My grandfather was a chief justice, a lawyer but he also raised hens so we had eggs and he was a carpenter and built things with his hands and he was a joker.”

Hattori and her eight siblings grew up in federal government staff housing where her father, Paul Mitsuo Hattori, was the staff geophysicist at the Guam Geomagnetic Observatory at Potts Junction in Dededo.

Focus on relationships

Her mother, Fermina Leon Guerrero Perez Hattori, is familian Titang and they would spend most weekends in Chalan Pago at her grandparents’ house.

There, she watched and learned from her grandfather, Joaquin Cruz Perez, who was an attorney, judge, legislative senator and the island’s first Supreme Court chief justice.

“He was very good at listening, worked a lot in family court and really wanted to provide safe spaces for voices of not just the parents but the children to come through,” Mary Therese Hattori said.

She added she learned from her grandfather that “listening leads to wise decision-making and action to achieve some sort of justice and harmony for people and families. Much of his work was centered on relationships, and I see this very much in the work my four brothers and four sisters do.”

She says her family are an ambitious bunch and are all doing well in their career paths.

In addition to herself, three of her siblings also have doctorates, including her oldest sister, Anne Perez Hattori, who is a professor of history, Micronesian studies, and CHamoru studies at the University of Guam; her twin sister Margaret Hattori-Uchima, dean of the school of health at UOG; and her brother, attorney Stephen Hattori, who is the first CHamoru to lead Guam Public Defender Service Corp.

“How do you keep nine children occupied and out of trouble? You give them things to do and ways to pursue their passions,” Mary Therese Hattori said of her parents, who “are really good at identifying our different interests and passions.”

Parents support passions

Growing up, she was into computer science and coding, while her identical twin loves science and medicine.

“You learn where your strengths are and where the strengths and interests of your younger brothers and sisters are,” she said.

“We had this practice growing up, there were nine of us and each one of us had a chore, and you were stuck with that chore for a year or until all the siblings called a family meeting and we negotiated swapping chores.”

Not living in a traditional Guam village or neighbor also presented its challenges.

“We lived in a remote area, sometimes with no neighbors. It was just the nine of us and you had to get along or you had nobody to play with,” she said.

“We learned how to collaborate, how to get along, and how to negotiate with each other. And if you were older, you had to learn to prevent the fight among the younger siblings and to keep the harmony going in the family.”

“I think the way I operate now is more a reflection of the way I grew up and the way we experience life,” she said of the life lessons she brings to the table with her work supporting 20 Pacific Island nations, territories and the state of Hawaii.

‘A holistic approach’

She has expanded the word development from its traditional focus of economic or governmental development to a more integrated model.

“We take a holistic approach to development and look at the whole person and the whole environment, because our well-being is dependent on so many factors. We are looking at development through the arts, through education, through social programs,” she said.

“Also, what does the technology infrastructure look like across Oceania and how can we help advance digital equity, digital literacy and the use of block chain ledgers and crypto currency for financial operations of a country. And what might be the benefits and risks and challenges associated with those sorts of technologies.”

They recently hired two Oceania research fellows with expertise in climate, climate science and climate migration. There are ongoing grassroots efforts helping communities in Hawaii hit hard by COVID-19, particularly the Filipino and Samoan populations.

And according to Hattori, there is documented and anecdotal evidence of a rising tide of discrimination against Micronesians in Hawaii across many sectors.

“There is a diminishing sense of ‘aloha’ for Micronesians in Hawaii, a rising level of discrimination, inequities in terms of access to medicine and education, targeting by the police department, and a lot of hate speech in social media,” she said.

“So a lot of my work is around educating the public, educating people in public service, school teachers, service providers — helping them better understand and support Micronesian families.”

Fuetsa pålao’an

But Hattori’s true calling is championing the innate qualities of her fellow Pacific islanders.

“Much of my work is around helping people understand that these Pacific nations are filled with people with names and faces and powerful stories and history and part of our job is to bring those stories to the fore and raise awareness about some of the challenges that we are facing but also to bring forth those stories of life-affirming, positive cultural traditions and practices that can help improve societies across the planet.

“We are the original caretakers of the ocean and the land and we have all this deep indigenous knowledge around caring for our environment; some of that knowledge can help address climate change problems.

“In the Marianas we come from a matrilineal society and we have perspective toward women. Fuetsa pålao’an, the power of the women. We uphold our women in a different way than you see in America and in other places in the Pacific where women are not treated well and where we have sorts of problems of gender inequality.”

Her passion unabated, she added, “My job is to be that bridge across cultures and take the best of all our cultures across east and west to help make the world a better place.”

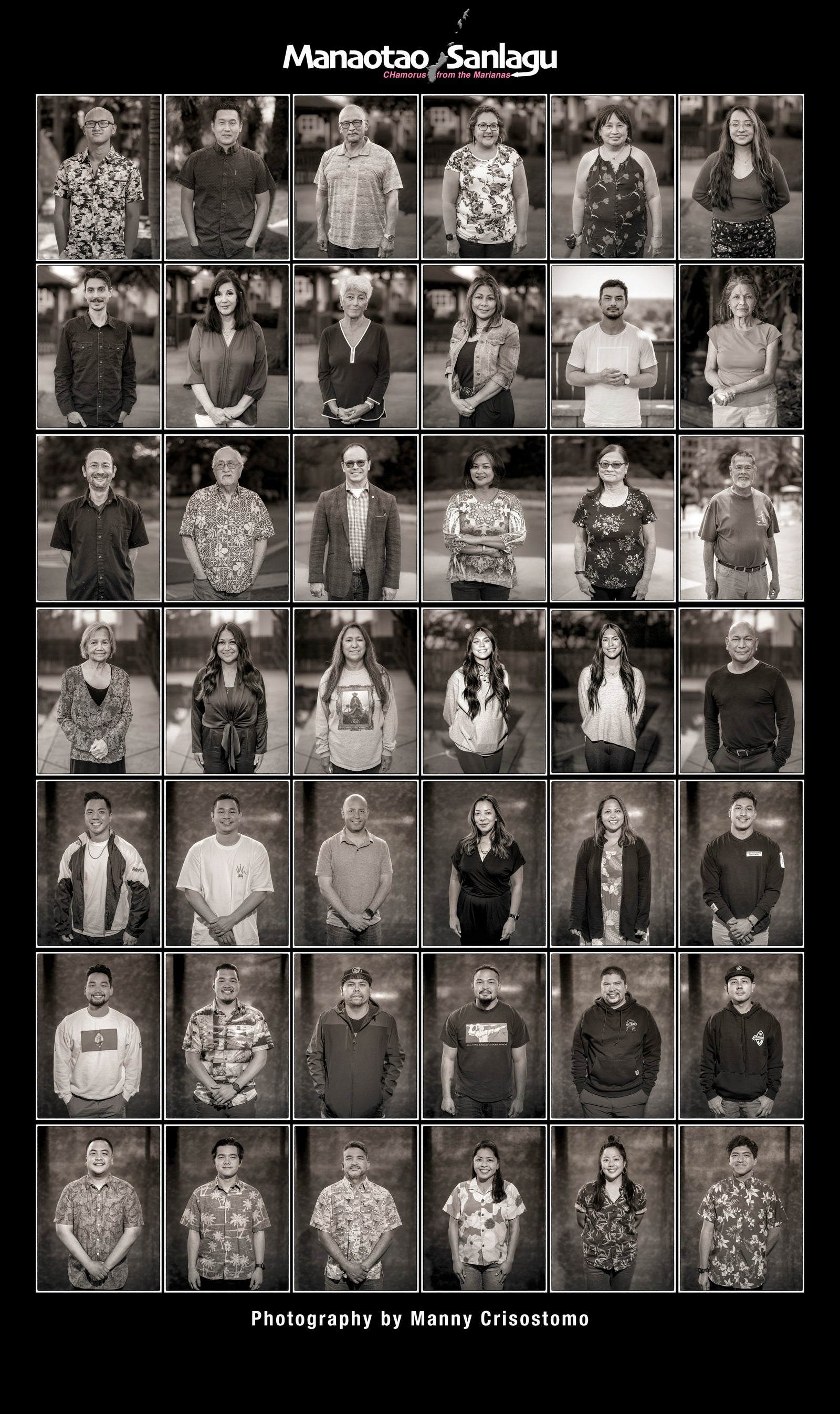

Manaotao Sanlagu is Manny Crisostomo’s ongoing visual documentary of CHamorus from the Marianas living overseas that is featured weekly in the PDN. If you or someone you know would like to be part of this documentary or wish to support this project, contact Crisostomo at sanlagu.com. The project is sponsored in part by Brand Marinade, a CHamoru-owned creative agency in the San Francisco Bay Area.