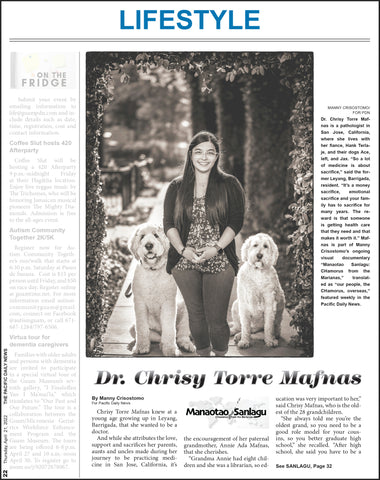

By Manny Crisostomo

Chrisy Torre Mafnas knew at a young age growing up in Leyang, Barrigada, that she wanted to be a doctor.

And while she attributes the love, support and sacrifices her parents, aunts and uncles made during her journey to be practicing medicine in San Jose, California, it’s the encouragement of her paternal grandmother, Annie Ada Mafnas, that she cherishes.

Chrisy Mafnas graduated with honors with a biology degree from University of Guam and left island to do biomedical research at Scripps Institute of Oceanography at UC San Diego.

“I told her I wanted to go to medical school and she said, ‘Well, you’ve already graduated college but you could still show your cousins that you can do more,’” she said.

While working at Scripps she found out she got accepted to medical school and was excited to share the news with her grandma.

“I was working and later that night I called and told her I got into medical school and like, four hours later she passed,” she said.

“It was definitely bittersweet because I was super close to my grandma,” she added. “Super excited that I got into medical school, but super sad that she had died. I had to get on the plane two days later to Guam for the funeral.” Annie Ada Mafnas was 72years old when she died of breast cancer.

‘Definitely more stressful’

Chrisy Mafnas received her medical degree in 2010 from University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine followed by a four-year residency in anatomic and clinical pathology at the Hawaii Residency Program.

She also completed two fellowship years at Stanford University in gastrointestinal/surgical pathology and cytopathology.

She is currently a pathologist at Kaiser Permanente Santa Clara Medical Center and lives in San Jose with her fiance, Hank Terlaje, and their two dogs, Jax and Ace.

“I love what I’m doing but it’s definitely more stressful than I had anticipated,” she said. “We’re human, right, and everyone’s going to make a mistake. And when your mistake is affecting another human being, it makes it very, very tough. So our margin of error has to be very, very slim.

“It’s a win for me to wake up every day and not make a mistake.”

Early days

The 42-year-old is the oldest of two born to Kathy Torre, familian Manila, of Dededo and Vince Mafnas, familian Balaku, of Leyang, Barrigada.

Growing up, she said, “health and science classes came easy and I just found the body fascinating. I don’t have any, like physicians in my family or anything. So I had no idea what I was getting myself into. But I knew I liked science, I liked health and I wanted to help people.”

The first inkling was when as a fifth grader at Cathedral Grade School, she understood her paternal grandfather, Bernardo Leon Guerrero Mafnas, had lytico-bodig and was part of national research study of the neurodegenerative disease that was unique to the island.

“I knew when I was really young that my grandfather was involved with this research study where when he died, they were going to take his brain and study his brain to see if they could find a cure for the disease. And I thought, ‘That’s kind of cool,’” she recalled.

TV science shows

In middle school she was obsessed with PBS science shows and Discovery and Discovery Health channels.

“I remember one particular time they were doing some weird surgery and the person was on the OR table and you know, there’s blood all over the TV,” she said.

“I wanted to watch it but I know I’ll get in trouble. And my dad’s like, we’re not watching this during dinner, turn it (to a different channel).”

It would take almost two decades to realize her dream.

“I graduated high school in 1997 and I was 26 when I started med school,” she said. “I didn’t finish all my training until 2016, so I am only five, six years into my career as a pathologist.”

All those years she said that “100% never thought about quitting,” but she was homesick and it was especially difficult during the holidays.

Taste of home

She found out that cooking eased her mahalang.

“That’s what has helped me stay not as homesick,” she added. “If I’m craving something, I just make it. I appreciate that they kept me in the kitchen and taught me how to make chalakiles and titiyas and påstet, So whenever I feel like I need a little bit of home I just make it myself.”

In addition, she learned how to barbecue from her dad and how to make potato salad, shrimp patties, eskabeche and kalamai from her grandmother and aunts.

“The holidays are particularly hard. But I learned and now make boñelos dago every year for Christmas,” she said. “And I force myself to make some kind of new CHamoru dish every year.” She’s now added manha titiya, apigigi and rosketi to her menu.

Being the first doctor in her family means phone calls and WhatsApp chats from relatives about all sort of ailments.

Monitoring from afar

She was happy to oblige, and during the COVID pandemic Mafnas was particularly concerned for her family in Guam.

“I felt helpless and had anxiety because it was unknown — before the vaccinations came out — and people were getting it pretty bad,” she said.

“I bought pulse oximeters and thermometers and a bunch of other things and I sent them to Guam. And they’re like, ‘What is this?’ And I said, ‘Just hold it. Because if any of you get COVID, I’m going to have to monitor you from California.’

“And then the first person that got COVID, I said use the pulse oximeter. And they’re like, ‘What am I looking at?’ I said just tell me the number on top and the number on bottom. That’s all I need to know, they’ll tell me and I’m like OK, you’re fine. You don’t have to go to the hospital yet. So I was able to monitor my family from afar.”

Throughout it all she has remained humble and credits her family for her success.

“I didn’t do this alone and I don’t come from a huge family of doctors,” she said. “I had no idea what I was doing or what route to take, but I knew I wanted to do it. So I just figured it out as I went along and worked really hard. And if I can do it, anyone can do it.”