By Manny Crisostomo

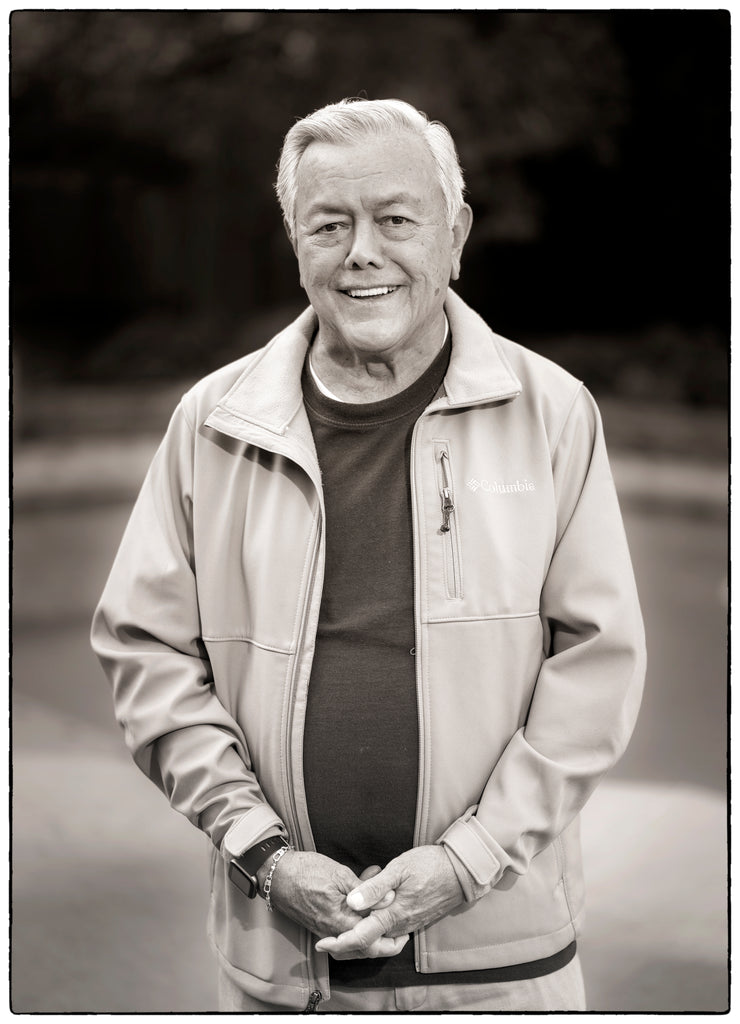

On an unseasonably warm November morning in the San Francisco Bay Area, Arthur Anthony Jackson Sr. was playing a round of golf with his sons, daughters and grandchildren.

At about the eighth hole, they let another group play through and one of the men approached him. “He came up to me and said, ‘Hey, I heard somebody is having a birthday here.’ ‘Yeah, that’s me.’ And he said, ‘How old are you gonna be?’ I said, ‘I’m turning 80.’ He says, “Oh, I love that number.’”

It was when they were taking pictures together that Jackson realized his well-wisher was former San Francisco 49ers wide receiver Jerry Rice, who famously wore No. 80.

It was a serendipitous meeting with Rice, widely considered to be one of the best players in the history of the National Football League. And it wouldn’t be much of a stretch to suggest that Jackson’s life and accomplishments, albeit not on the football field, would equal that of a legendary NFL Hall of Famer.

Jackson’s legend began as a young World War ll survivor on Guam. He was born two weeks before the Japanese occupation of the island and suffered with the family in the Maite area. His grandfather, a former Marine, was captured on Guam and sent to Japan as an American prisoner of war in 1941. His grandfather was released in 1945, following Japan’s surrender.

The year before that, the Japanese rounded up all the CHamorus throughout the island and forced them to the Manenggon concentration camp. That long march was one of the worst wartime atrocities on the island. Thousands were herded to the camp — with very little possessions, no food and no water —- and were beaten if they strayed off the trail.

“I remember my dad and mom talking about marching to Manenggon when I was about 3 ½ years old,” Jackson said. “My dad was carrying my sister Lillian, who was just a baby, and they looked back and they saw me walking, and they said, ‘Where are your shoes?’ And I said, ‘I don’t know, I lost my shoes.’ I was barefoot and we were walking through the jungle, because there’s no road or anything to Manenggon.”

Jackson and his family joined more than 18,000 other refugees at the concentration camp along the Manenggon river. On July 21, 1944 US military forces liberated the island and freed them.

“Growing up in Guam, right after the war, the military was such a prominent presence in our lives, and I definitely wanted the military lifestyle, to be in uniform,” Jackson said. “But again, on my mother’s side, they’re all educators. The Untalans were all in education, my aunts, my uncles, all my mom’s siblings. And I enjoy being in a classroom, working with kids.”

His affinity for education and the military would show up over and over in the next half century of his life.

The early years

Jackson is the oldest of four siblings born to Arthur Abraham Jackson of Hagåtña and Antonia Leon Guerrero Untalan Jackson, familian Casimiro, also of Hagåtña.

Over a decade after the war ended, the family, including his grandparents, left Guam for San Francisco. “In 1955 we left on Transocean Air Lines from Guam to Midway to Wake to Honolulu to Oakland (airport),” Jackson recalled. “The (Guam) airport was a little dinky Quonset hut and everybody’s there because we were leaving and we weren’t planning to come back.”

But Jackson did come back to Guam 10 years later as a member of the California National Guard and a junior from San Francisco State University. “I needed to have a deferment (from the Vietnam War) and so I decided my chances are better to go to school in Guam because I had already married and had a son.”

Working toward his bachelor’s degree in history at night at the University of Guam, he took teaching jobs at New Piti Elementary School, Agana Heights Elementary School and Agueda Johnston Junior High School. He later left the Department of Education to take a job as a financial aid officer at UOG.

The UOG president at the time, Antonio C. Yamashita, suggested to Jackson that if he wanted a career in higher education, he should get an advanced degree. Jackson heeded his advice and enrolled at Yamashita’s alma mater, the University of Northern Colorado.

He secured financial aid with GovGuam’s Professional/Technical Award Program, which not only supported his schooling but also his wife and four children who accompanied him to Greeley, Colorado.

‘It wasn’t easy’

He received his master’s and doctorate degrees from the university and is especially proud of his doctorate in higher education and student personnel administration.

“When I got mine, I think you can count the number of CHamorus that had doctorates with the fingers in both hands,” he said. “That was a struggle, it wasn’t easy. And you know we have to keep trying to do better, to keep trying to make our island better.”

He returned to UOG with doctorate in hand to fulfill his PROTECH award requirements, and took the dean of students position, which he cherished.

“I had ideas I wanted to try out when I came back,” he said. “I was full of energy and I wanted to implement a lot of these things like student housing, registration and admissions, financial aid, student government and job placement.”

Four years later he couldn’t turn down a chance to use the psychology, counseling and guidance skill sets honed from his advanced degrees when then Gov. Paul Calvo asked him to be director of the newly created Department of Youth Affairs.

But it meant leaving his Dean of Students job. “I really miss the students and I thought we had great rapport,” he said. “He still has a trophy given to him by the student body. ‘It says the University of Guam Student Body Association, President's Award to Dr. Arthur A. Jackson 1976 - 1977’. I have this baby and I've kept it and, you know, this is something that I'm really very proud of.”

At the end of the Calvo administration, though, he had to quit his appointment at DYA. “Nobody wanted to hire me after Paul lost the election, because everything’s political,” he said. “I got into counseling with the Department of Education to try to make ends meet.”

As luck would have it, in the early 1980s Democratic U.S. House Delegate Antonio Won Pat’s bill to establish a National Guard unit on Guam passed Congress and was signed by the president. It was an opportunity to pursue his other love, the military, and he enlisted in the newly created Guam National Guard.

With all his credentials, he got a direct appointment as captain and quickly rose through the ranks, culminating as a colonel and U.S. property and fiscal officer for the Guam National Guard. He eventually retired after 20 years in 1999 as full bird colonel.

But he couldn’t sit still and returned to education teaching at Truman Elementary School for a year. He then went back to UOG as financial aid officer and acting vice president of student life.

In 2003, he and his second wife of 40 years, Doris Dydasco Reyes Jackson, both retired from GovGuam. They moved to Virginia to be near his son, Mike, and his grandchildren, but he didn’t stay retired long. He went back to work as a contractor for the Department of Defense and enjoyed lobbying state legislators to pass legislation that would benefit military families.

“The contract with the DOD was only for three years,” he said “After that, we decided, hey, I’m already a certain age, let’s wrap things up. Let’s go to San Antonio, because it’s kind of midway between the East Coast and the West Coast, and we have family all over the place.”

That was in 2008 and since then, he’s been teaching adult basic education; learning Castilian Spanish, the language of his grandmother; painting; hitting golf balls; playing in a band; serving as an active member of the Knights of Columbus; and traveling around the world and checking off places on his bucket list. Coming up: a future trip to the Holy Land and Santiago de Compostela in Spain.

And, after 30 years of research he finally published a book on his grandfather, “Biography of Arthur W. Jackson 1880 — 1961: An American Pioneer in Guam.” He presented the book to the Micronesian Area Research Center on Guam a few years ago.

“You gotta keep busy; like (former Gov.) Paul Calvo says, ‘You have to keep pedaling because once you stop pedaling, you fall off the bike,’” he said.

‘All you can ask for’

The day after his encounter with Rice at the golf course was Thanksgiving, his actual birthday. His simple birthday request was for paella that his Castilian grandmother, Dolores Herrero Kamminga, used to make.

But the kids went beyond, converting the back yard into an elaborate Castilian theme night and hiring a chef who specializes in making paella. Over 30 family members including a dozen of his grandchildren got all dressed up, his daughter-in-law did a flamenco performance, they played guitar and all sang his favorite song, “Yellow Bird,” then showed a video tribute of his life.

“It was really quite something that the kids, you know, orchestrated the whole thing and were able to put that together,”

I asked him how it feels to be 80, this milestone in his life.

“I don’t know how 80 is supposed to feel, never been there, never done that,” he said. “I just take it a day at a time, you know, at this stage, you do reflect, reflect on what’s happened in your life and everything. And thankful and blessed with a loving family, five kids, 13 grandkids and one great-grandkid, with another on the way. And the kids are doing well. That’s all that you can ask for.”