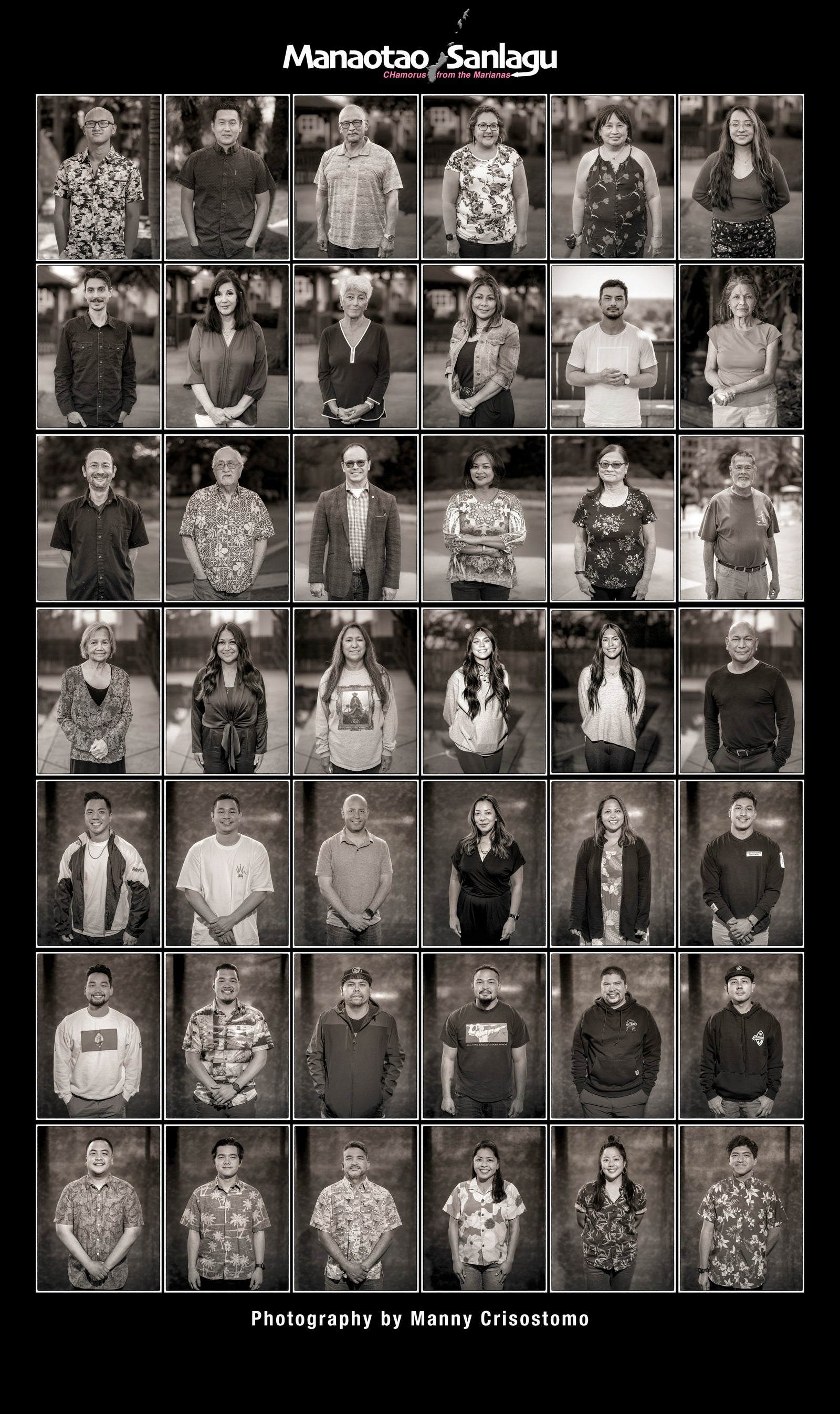

Manaotao Sanlagu: CHamorus from the Marianas

by Manny Crisostomo

In 1991 I wrote in my book “Legacy of Guam: I Kustumbren Chamoru,” “Oh, to be home again. We Chamorus have a word for such yearnings. ‘Mahalang’’ speaks of missing someone or something. It stirs a number of feelings inside me – loneliness, homesickness, a longing for the familiar. I see a lifetime of images of Guam compressed within the time it takes to utter the phrase, ‘Mahalang yu’.”

Three decades later I find myself again very mahalang but do not have any realistic way of moving back home to Guam like I did 30 years earlier. A friend of mine told me that feeling is a common, almost universal, one that CHamorus away from home speak about.

She suggested that I mitigate this by replacing this intense sense of longing with a sense of belonging. She said to find people with similar experiences. Find CHamorus, connect with them and be mahalang together — and in the process, find a sense of belonging.

This transition from longing to belonging is the crux of my new work.

It’s a simple premise: To photograph and share the stories of CHamorus from the Marianas living away from the home islands in a visual documentary, “Manaotao Sanlagu: CHamorus from the Marianas” — translated as “our people, the CHamorus, overseas.”

The goal is to find and connect with Mariana Islands CHamoru who uprooted, moved off island and relocated to communities across the United States and around the world.

Making connections

I wanted to find out if their decision to migrate and their journeys were unique to them and their families, or if there were similarities to that of the 180,000 other CHamorus who placed roots across the country and around the world.

I was curious to find out if they continue to observe and practice their island cultural traditions in either small or grand gestures. And if the CHamoru tenets of kustumbre (communal and familial values), ayuda (consensus building), inafa’maolek (interdependence and unity) and chenchule (reciprocity) endure in the diaspora.

What I found along the way humbled me as I met leaders in government and military helping shape our world; business entrepreneurs excelling while also giving back; and standouts in medicine, law, engineering, journalism, entertainment and hospitality thriving in their stateside communities.

They include Peter Gumataotao, retired rear admiral of the U.S. Navy. “I have been away from home so much and for so long, but I have this bond and this tie, as well as my family does, every time we go back that tie is still there, it’s always there, it will never go away.” “ Gumataotao is now in Hawaii and director of the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, which deals with Indo-Pacific regional and global security issues.

They also include restaurateurs Shawn Naputi and Shawn Camacho, who in their 20s opened Prubechu’ — a CHamoru restaurant in San Francisco, one of the top culinary cities in the world. “We did it with a dream, with a passion for hospitality, a passion for our culture and with a vision to say that we are going to put CHamoru food on this pedestal in San Francisco,” said Camacho.

I am heartened to see CHamoru artists proud of their roots carrying the torch of native storytelling and showcasing their art in brick-and-mortar venues and online platforms.

Fran Lujan, who heads the Pacific Island Ethnic Art Museum in Long Beach, California, sees the CHamoru identity struggles that diaspora artists have and helps them channel that angst. “It is my journey to help, help them to find that truth, in the best way that I can, which is through the way of the arts. Our artists, the work they do is breathtaking and it’s really a way our diaspora can connect with where they are from”.

I am inspired by the league of CHamoru scholars filling the ranks of academia in colleges and universities across the country writing discourse and publishing papers and books about indigenous cultures and Pasifika-centric voices and sensibilities.

“There is a growing network of indigenous scholars and we are identifying ourselves through professional associations. Identifying ourselves as guiding stars across the globe, the guiding stars that will guide the young emerging scholars through their journeys, their wayfinding through academia,” said Mary Therese Perez Hattori, interim director of the Pacific Islands Development Program with the East-West Center in Honolulu.

“Our studies are not for our academic benefit and not for career advancement but they are for the benefit of our people, we are raising awareness about our people and our cultures for the betterment of society.”

I am roused after meeting a growing number of stateside activists who are fierce in defending their CHamoru identity, and defiant and proud when shouting their voices thousands of miles away against colonization, militarization and climate issues.

“I consider myself CHamoru, I don’t consider myself a diasporic CHamoru, I consider myself a CHamoru that was born and raised not on her island. I have influences from here and I miss home, but at the same time I have been able to find ways to keep that connection,” said Lyn Aflague Arroyo, who spent over 20 years working in education, community outreach, and advocacy in the Bay Area, which gave her the opportunity to hear and learn from hundreds of migration stories.

I am aware that there are also tens of thousands of CHamorus who have never been to Guam or the Northern Marianas. An increasing number of these “sanlagu-born generation” members are searching and reclaiming their identity.

Many whom I have talked to would jump at a chance to visit their ancestral island homes but are hindered by the high cost of airline tickets. For those who have made an island pilgrimage, their experience back in ancestral lands gives them a renewed sense of appreciation of the complexity and richness of the CHamoru heritage.

Heidi Chargualaf Quenga is an accountant but volunteers all her free time directing the Kutturan Chamoru Foundation in Long Beach, which provides tuition-free dance, language and music classes on culture and traditions. A “fa’fa’någue,” or certified CHamoru instructor, Quenga works tirelessly to teach the CHamoru dance to students young and old living stateside, and helps raise funds to bring them to Guam to perform.

“I had the opportunity to bring home kids that have never been home for the first time. The shock, the surprise and even the tears that they have when they get there and just seeing them like wow this is where I am from, where my ancestors are from is a feeling I can’t explain because it is just amazing to see it.”

Manifesting culture

I am in the early stages of this documentary, following a trail of Marianas bloodlines as I plan to photograph and interview as many CHamorus as I can in the years to come. In lightening my mahalang, my longing, and moving to belonging, I witness the marvelous resilience of our culture manifested and revealed when we talk stories and cook our foods as we gather in our extended clusters. And when we get tattoos for our bodies, wear island motif apparel, put Guahan stickers on our cars.

When we reach out on FaceTime and Zoom, on chat groups and social media CHamoru-centric groups, we are connecting not only to CHamorus from the Marianas but our brethren across the street, city and states we live.

And when we gather at annual CHamoru events organized in communities like San Diego, Long Beach, San Marcos, Sacramento, Seattle, Tacoma, San Antonio to celebrate Mes CHamoru, PIFA, Chelu Festival, San Roque fiesta and Guam Liberation Day among others.

Lita Cruz Salas recently relocated from Mangilao to Killeen, Texas, and is mahalang but has quickly embraced her stateside belonging. “Let’s perpetuate what we as CHamorus have always grown with. Our sainas, they taught us respect and inafa’maolek. Wherever you go on this earth you always have your roots on Guam — i hale’-ta.”

Next generation

The other day I was enjoying a CHamoru fiesta-style meal at San Francisco restaurant Prubechu’ with Joe Castro and his family. Castro, 72, a retired licensed land surveyor from Alameda, told me that when he was 4 years old, his father, who was in the Navy, was reassigned to the West Coast and the family left Guam in 1952 aboard the U.S. Naval Ship General Edwin D. Patrick.

The family eventually set roots in Alameda and every year since the 1960s, the Castros, along with Manibusan and Duenas families who all ironically lived on Pacific Avenue, host a party cooking Guam foods, sharing updates about family back home, and telling stories of CHamoru life back on the islands.

Joe’s two sons, Jay and Jeremy, who have never been to Guam soaked it, and grew more curious as they got older.

“It’s amazing it took this next generation, the first generation born here, to grab a hold of the culture so strongly,” he said. “I just assumed my heritage, whereas as these guys they pursued it.”

‘I am home’

A couple of years ago Jay Castro organized an extended family trip to Guam, a long overdue trip to their ancestral home to visit friends they made virtually and relatives they have never met. I asked Joe Castro what it was like, leaving Guam as a young boy and finally going back 65 years later.

He started saying, “Well, when we landed and went outside and you know I said …” and the gravity of that memory and that moment took over as his voice cracked and tears welled up. After wiping his tears, Joe finished his thought and murmured “I am home, I said I am home.”

In the weeks, months and years to come I will present the faces and voices of those “Manaotao Sanlagu: CHamorus from the Marianas,” This is a visual documentary to collectively show our CHamoru-ness to the world and to ourselves.